Contemporary period

1850 : The beginning of wine sales

Up to this point, wine wasn’t sold. Production covered daily needs of households. Starting in 1500, a timid regional trade began, to supply inns and the part of Upper Valais that did not produce wine. Some enterprising owners experimented with techniques to improve the quality of the wine, make their vineyards more profitable and to find new outlets.

The development of commercial trade in grapes and wine in Valais began as a result of the Sonderbund civil war in 1847. The lands taken from the Church were bought by wealthy Valais families and investors from canton Vaud; they founded the first viticulture businesses in Valais. Canals built for the Rhone river offered the possibility of enlarging the grape cultivation area. The railroad’s arrival at the start of the 1860s opened new possibilities.

1850-1918 : the rapid rise of grape and wine trade

The development of commercial trade in grapes and wine in Valais began as a result of the Sonderbund civil war in 1847. The lands taken from the Church were bought by wealthy Valais families and investors from canton Vaud; they founded the first viticulture businesses in Valais. Grape varieties planted and cultivation methods evolved. The state actively encouraged agricultural progress, including growing grapes. The first correction of the Rhone river and the building of the rail line at the start of the 1860s offered the possibility of enlarging the growing area and reaching new markets. Viticulture very quickly became the most important branch of Valais agriculture.

1918 : Rebuilding the vineyards

Oidium (powdery mildew) and downy mildew start to contaminate the vineyards in Valais in the 1880s. Phylloxera, which has ravaged Europe’s vineyards, arrives late in Valais (1916). Preventive measures have already been taken, but progressively rebuilding the vineyards has become necessary. As elsewhere, plants grafted onto American rootstock that is resistant to phylloxera must be planted. Selecting rootstock plants that are compatible with local grape varieties involves long years of experimenting. The older indigenous grapes are left behind for plants that are more profitable and easier to grow. Fendant, Rhin and Gamay are among the most popular grapes for new plantings. Virtually all of the Valais vineyards are rebuilt by the end of the 1950s.

1918-1950 : big changes

The first half of the 20th century is, for viticulture, a rich and dynamic period. After the arrival of phylloxera in 1916, the vineyards were rebuilt in a few decades. The grape varieties planted and the viticulture techniques used changed profoundly. A major economic crisis in the 1920s that forced wine producers and wine businesses to organize themselves is behind the creation of cooperative winery Provins. The federal government also played a growing role in the wine industry. Training became more professional. The area given over to growing grapes was enlarged, so much so that Valais became the largest wine-producing area in the country in 1957, with 3,550 hectares.

1930 : Cooperative Provins created

Valais suffered from a flood of wine on the market after the First World War. The surface area given over to grape cultivation continually grew and harvests were very abundant (24 million litres in 1918). Stocks were a burden for wineries and the market was awash with foreign wines. Valais wines had trouble finding buyers in a Switzerland impoverished by the economic crisis. Producers, caught by distributors’ rules, were being strangled by the system. They decided to unite, with support from the authorities. The “Fédération des Caves coopératives valaisannes” was born in 1930; the cooperative group became “Provins” in 1937.

The goal was to ensure a fairer selling price for producers and to give them the option of making the wine and storing it. From the start, the cooperative asked its members to submit to a certain number of rules in order to improve techniques and the quality of the end product. Provins was largely responsible for introducing a zoning plan for the vineyards and the use of wooden crates.

1950-1991 : tensions rise over quantity vs quality

The second half of the 20th century was characterized by an increasingly structured organization to produce and sell wine. The constitutional basis for a federal viticulture policy that was protectionist was created at the legislative level. The growing area for wine grapes in Valais continued to increase steadily, reaching 5,200 hectares by 1980. Production became industrialized. Harvests paid off and the world of grape growing knew a period of prosperity. Emphasis on yields often overrode consideration for the quality of wines, however.

During the 1980s Valais, like other wine-producing regions, suffered a serious problem of over-production, with major consequences for regulations and quality. The 1982 and 1983 harvests were very abundant, causing prices to drop, with excess stocks – the financial cost for wineries was enormous. The entire viticultural world was shaken by the crisis, prompting serious questioning about the way it worked.

From 1991: the creation of the AOC system

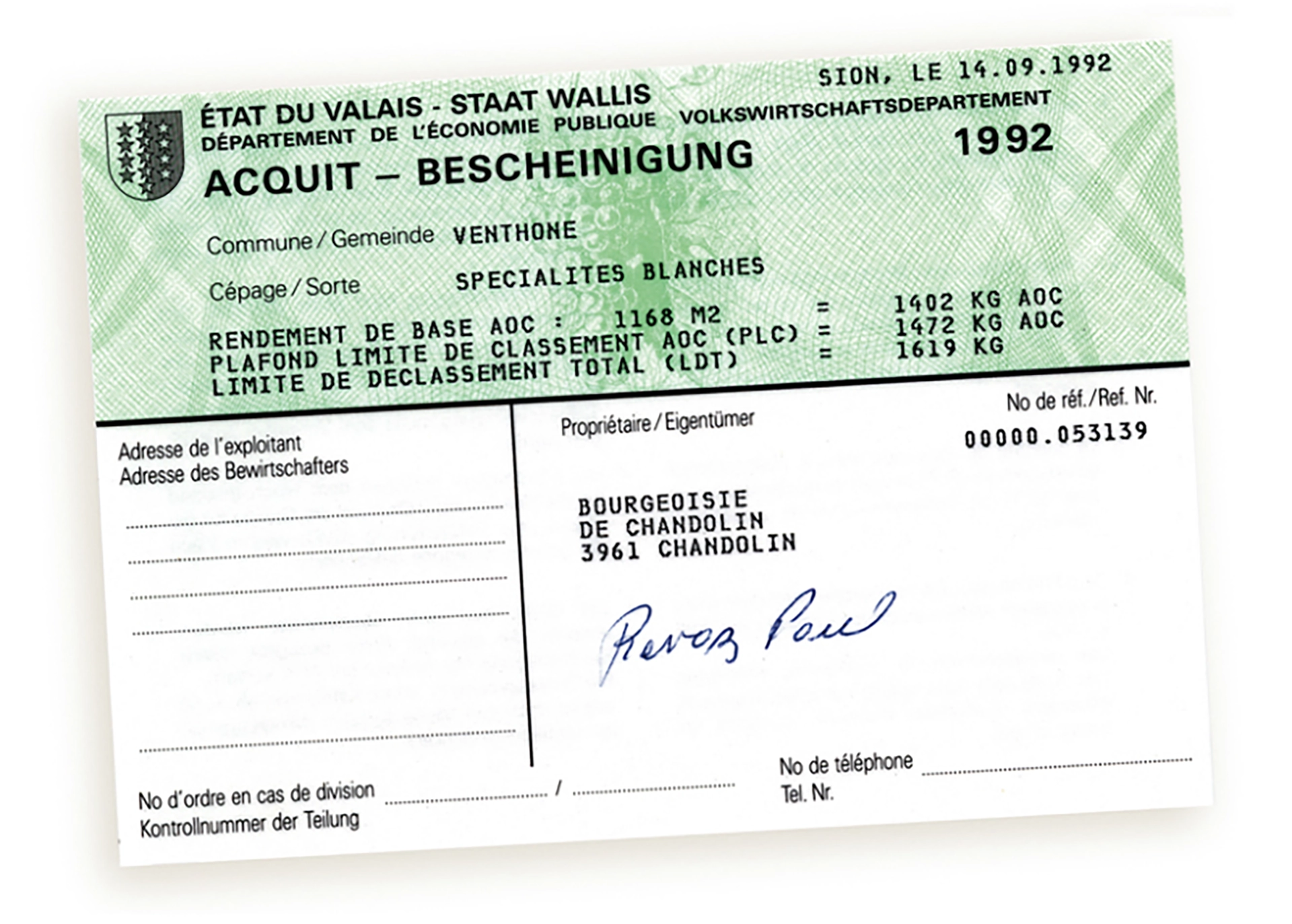

The major sales crisis of the 1980s led to the establishment of controlled designations of origin (AOC). These were implemented in Valais in 1992.

The purpose of the “Appellations d’Origine Contrôlée” (AOC) system is to guarantee the quality and the authenticity of Valais wines. Harvest yields are now limited to set weights per square metre. Quality control systems with checks, regulations and production areas adapted to grape varieties are in place.

Valais wines have an important card to play in the context of freer markets with more imports and greater competition: they are notable for their quality, but also their originality. The 1990s were marked by the return on a large scale of Valais specialty wines, from ancestral grape varieties, wines of great oenological quality that seduced wine tasters from around the world.

In addition to the revaluation of indigenous grape varieties, the promotion of terroirs and the preservation of the landscape heritage are also part of the objectives of Valais’ viticultural policy at the dawn of the 21st century.